It’s important at this point in the discussion to outline Mahabir Pun’s philosophy with regards to his work principles. Over the years Mahabir Pun has worked with dozens of private, governmental, non-governmental (NGO), international profit and non-profit organizations (INGO) on various projects. This is what he has to say about choosing to work with an organization: “I am open to any individuals or organizations to do anything and I can work with them without any formal condition. I don’t chose projects but I just do things that I think is good to do. I don’t even look for their background of the people who come to work with me. Everybody can come and work with me. It is okay even of they don’t put any inputs. I just want them an opportunity and want to learn something from the villagers. I don’t want to be picky. My only condition is that whatever I do, it should benefit the communities. I want others to behave the same way.”

Mahabir Pun puts as much effort into working with HEF volunteers, such as Gail from Australia, as he does with international organizations like The Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA).

In fact Mahabir Pun does follow his principles and examine the entity before teaming with any one person or organization. For example, before working with the Institute for Himalaya Conservation (IHC), he set conditions. He requested a place on the board of directors in order to steer policy and decisions. He required all projects use local villagers to implement, construct and run a project. This was in the late 1990s and I think he was beginning to understand his role as a leader and not just an entrepreneur. His success can be seen in the locally run cheese, yak, trekking, paper making, reforestation and dozens of small local enterprises successfully run by local rural villagers. He will not participate in projects that are just for profit, even for Nepal based companies. Everything he does benefits the poor rural population either directly or indirectly. Some of his critics believe he misses financial opportunities because he fails to understand that profit making is not necessarily an evil goal. There are companies directed to helping the world’s poor but still make a profit for investors. An excellent book on this topic is: “The Business Solution to Poverty: Designing Products and Services for Three Billion New Customers” by Paul Polak and Mal Warwick.

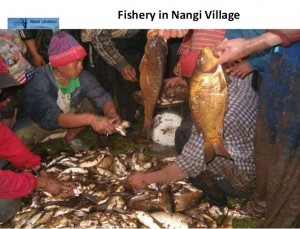

Nangi farmer carrying cauliflower to market. Through an IHC program local farmers can sell produce to Pokhara restaurants in an effort to promote local sustainability.

He is a staunch proponent of grassroots involvement and ownership of a project to assure success. He alleges most Nepali NGOs are corrupt. He stated; “The money raised is just a trickle to the rural areas. The money that goes to the real people is just a trickle.” He believes most of the money raised by these local NGOs is used for administrative costs such as fancy offices, expensive vehicles and “fat” salaries. The NGOs are run by city bureaucrats who have little understanding of the rural poor. He believes the NGOs exist to support themselves and actually make very little impact in rural areas. The same philosophy is argued in the disturbing book about the dark side of international aid written by Michael Maren in 2002 and called: The Road to Hell: The Ravaging Effects of Foreign Aid and International Charity. If you haven’t read this book I recommend borrowing it from your local library.

Mahabir’s solution: NGOs should be started by rural villagers; NGOs should be started by service motivated people such as expatriates from the villages. His solutions are challenged by the rural isolation and diversity of Nepal. The Nepal culture can differ from one village to another so what works in one place may not work in another. One way Mahabir has devised to bring entrepeunurial villagers together to discuss their projects, share challenges and solutions is to open the Nepal Connection in Kathmandu, which he described as a not-for-profit sharing company.

Join me next week for more about the Nepal Connection and how Mahabir Pun brought together diverse contributors from around the world to realize this dream.

http://www.nepalwireless.net/content.php?id=54